7 Critical Books for Developing a Philosophy of Technology

Media theory - from the gateway to the hard stuff.

Recently, I had a fantastic discussion about the dynamics of the current technological landscape and the future of artificial intelligence with someone I had not seen in a while. He asked that I provide him with some reading recommendations on the philosophy of technology, so I spent some time mulling it over to identify my favorite books, which have had the most significant impact on my views on technology.

These are not technical books. They will not detail the specific workings of contemporary technology. Instead, they are books that emerge from or are tangential to the media ecological tradition, which seeks to explore and understand how media influences man. These books are inconsistent with one another, with some even contradicting others on specific points. This is not a list of books that all fit into one worldview, but rather various worldviews that uncover one specific domain: media.

Media, as in that which mediates, information or otherwise, taking the form of various technologies.

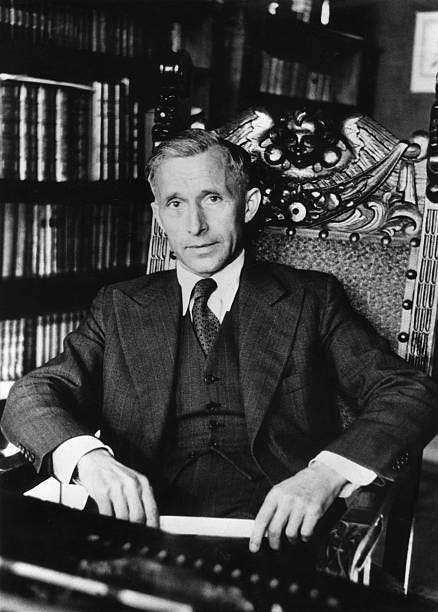

Technopoly

Neil Postman is the gateway drug into media ecology. His writing style is accessible, but his insights are scathing. Postman is best known for Amusing Ourselves to Death, in which he argues that television has warped culture, rendering all serious discussion into a form of entertainment. This thesis may have seemed questionable when published in 1985, but now geopolitics is litigated by the masses on TikTok.

Technopoly adopts a broader perspective, illustrating how technology generally dominates society. Technology is deified, and it shapes society as a whole to reinforce itself. Postman draws heavily from McLuhan, who is known for identifying how the manner of content transmission matters far more than the content itself: “the medium is the message.”

He examines the history of technological development, illustrating how tool-using cultures evolve into technocracies and ultimately technopolies. Postman identifies how new technologies have impacted the time and place of their invention or discovery up until the present day. Reading Technopoly enables one to shift his perspective on technology and recognize its hidden impacts.

Man and Technics

Man and Technics, one of Oswald Spengler’s final works, was meant to be part of a broader project of the prehistory of man. Although the entire project was not completed, this short book offers a unique perspective on the nature of technology and its relationship to the development of human society and humanity’s broader cultural ambitions.

Technics are not technology. Rather, they are “the tactics of living”: technics are the combination of tactics and means. Techniques include the tactics of an animal paired with its biological means, as well as human tactics and their artificial means. As I said in a recent piece on the book:

Man possesses the unique ability to creatively transform his materials into new tools that will serve his tactics. But it is important to note that the tactics do not come from the tools. Tools and machines flow from thoughts about processes (washing, hunting), not vice versa. Man’s technical machinations are critical to his existence in an otherwise cruel and punishing world. His struggle against the external world has given rise (and fall) to the high cultural drama we call history.

Read the rest here:

Spengler’s short book highlights the apocalyptic situation that the West has gotten itself into. The Faustian man pursues greatness without regard for the potential costs. As a result, the technical achievements of Western culture are sowing the seeds of its demise. Spengler provides a unique perspective on technology, connecting it to man’s inner will to power, and distinguishing how technics are employed by men of an aristocratic or predatory spirit versus those who embody the herd instinct.

Into the Universe of Technical Images

Vilém Flusser's Into the Universe of Technical Images examines how machine-produced images (whether by the camera or computer) redefine human culture and communication. He distinguishes between non-technical images, in which the image is the direct expression of the human hand against the cave wall or canvas, and technical images that are the product of computers and code.

Media shapes consciousness. A culture that relies primarily on text thinks linearly. With technical images, linear sequencing is broken, and images fail to depict the world directly. Technical images are coded abstractions, dependent on the apparatuses and programs that produce them.

This has profound impacts on society. Flusser warns that society may be overwhelmed by an information flood, an endless stream of images that replaces understanding with superficial data. Society becomes post-historical. Events lose narrative coherence and are consumed only as image-flashes.

Flusser’s observations about the impact of technologically concocted images are prescient in this era. Every week, AI image and video generation improves. Anyone can be made to say anything. Anything imagined can be produced, with no limits whatsoever. Coherence retreats into the past as the hallucinations of machines become our source of entertainment.

Simulacra and Simulation

Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation is hard to read. This is not least because Baudrillard seeks to encapsulate his thesis in his distinctive writing style. As everything is presented, and then re-presented, and then presented once again, but with no reference to the original, reality becomes hard to comprehend. In a way, it disappears entirely. Simulation replaces reality.

Baudrillard outlines four stages of representation:

The faithful image that reflects reality.

The distorting representation that masks reality.

That which masks the absence of reality, pretending to show something real when it's not.

The simulacrum that bears no relation to reality at all.

The procession of simulacra reigns. The world is experienced through simulated media before reality is encountered. Culture, media, and identity are all entwined in the progression of simulacra, becoming symbols in themselves to be consumed and exchanged.

Simulacra and Simulation reveals the underlying reasons for the increasingly self-referential nature of our world, the omnipresence of brands, and why you just saw a commercial for a Star Wars + Black Lives Matter collaboration Roomba.

Human Forever

Unlike all of the other authors on this list,

is alive and well (and on Substack). In Human, Forever: The Digital Politics of Spiritual War, Poulos draws from some of the thinkers above, as well as many others, to construct a spiritual understanding of the current media environment.Poulos argues that digital technology poses a threat to humanity's spiritual foundation. In the face of technological domination, man risks being torn from his flesh, disempowered, and replaced by artificial systems.

While many media critics only touch on spirituality and politics tangentially, Poulos identifies a deep connection between these areas. He critiques both globalism and secular liberalism for their roles in spiritual disfigurement. As an antidote, he underscores the importance of place, tradition, family, and flesh as remedies to the digital flattening of human life. He highlights narrative and memory, even recounting his biography in the second chapter, as defenses against the bare, data-driven drivel that emanates from digital technology.

In addition, man must remain in touch with Logos and refuse to give up his humanity. He must prioritize the continuation of his culture and heritage and strive to maintain owned space. Chimp in nature never… anyway.

Industrial Society and Its Future

Dr. Monzo and After the Hour of Decision disavow terrorism. That being said, Ted Kaczynski had an IQ somewhere around 170, and his critiques of technological society are scathing and challenging to grapple with. Kaczynski argues that the pace of technological evolution has outpaced biological evolution, resulting in man existing in an environment not only foreign but also hostile to his natural state of being.

Kaczynski argues that, because man no longer participates in the work done for his survival, he has become alienated. Needing a challenge, he fills his time with surrogate activities to experience the power process of goals, effort, and achievement. Man has become enslaved by the technology that was supposed to set him free. Advances in technology are accompanied by bureaucracy, regulation, surveillance, and specialization.

He also provides a remarkable critique of leftism, describing it as psychologically driven by feelings of inferiority, resentment, and a desire for control. Leftism is a symptom of technological society’s over-socialization and need for conformity.

Kaczynski sought to inspire a revolution through his terror attacks and manifesto, which ultimately did not happen. His critiques of technological society are probably correct, but ultimately impotent due to the totalizing nature of technology.

The Worker

Ernst Jünger wrote The Worker in 1932, but it was not translated into English until 2017. Jünger argues that bourgeois liberalism is collapsing and will be replaced by a new metaphysical force in the form of the Worker. The Worker has been shaped and created by the process of industrialization, technological advancement, and the total mobilization of World War I.

Jünger’s Worker is a new anthropological form, defined by discipline, will, efficiency, and technical mastery. He embodies the metaphysical principle of work in the world of total mobilization. War, labor, and even leisure become subordinated to collective effort and discipline.

Technology plays a critical role in this process. It is not neutral material, but rather the means tied to the new metaphysics of work. It expresses the will-to-form of the Worker. Jünger argues that this is destiny. Total mobilization, total technological domination, and the destruction of liberalism are inevitabilities that must be embraced.

The new world will be anti-liberal, anti-democratic, and anti-individualist. The bourgeois world of comfort, commerce, and freedom is weak and decaying, and cannot defend itself against the new ethos of the Worker: disciplined heroism, hierarchy, and sacrifice.

Jünger’s radical rejection of liberalism, modernity, and bourgeois values is gripping. The book is dense but provides a unique perspective on technology and its impact on society and the political order.

As I stated in the introduction, these seven books do not neatly fit into a distinct worldview, but instead offer different perspectives on technology. They are also not the definitive best books on philosophy of technology, but rather, they are all books that have had a significant impact on my outlook.

I should also mention McLuhan. He did not make the list because I have only read essays by him, never a complete book. I did not want to recommend a book that I had not read all the way through, but many of the essays by him that I have read are in Understanding Media (1964).

A good list, here are a few more.

The Technological Society, Jacques Ellul

The Question Concerning Technology, Martin Heidegger

4 Arguments against Television, Jerry Mander

The Gift of Good Land, Wendell Berry

The Arrogance of Humanism. David Ehrenfeld

The Myth of the Machine: Technics, Lewis Mumford

I’d have to add Heidegger the question concerning technology. It is the most philosophical of all of these