Invasion

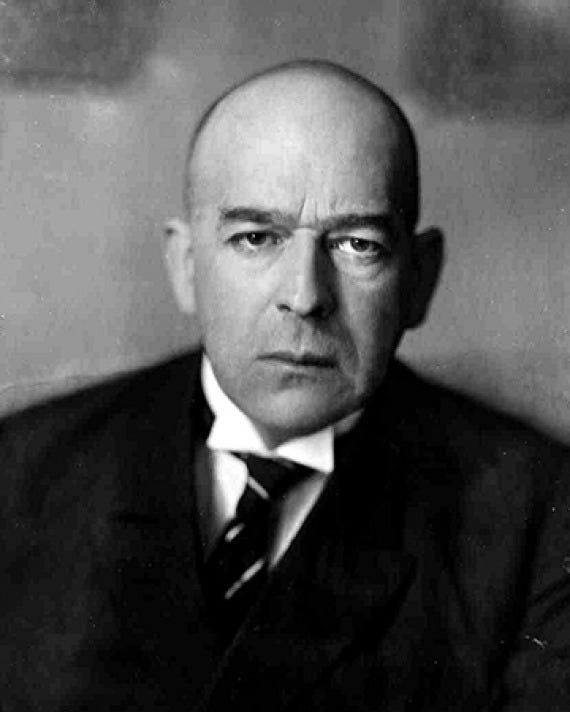

Oswald Spengler's 'The Hour of Decision' Series - Part 16

Part 4 of Spengler’s The Hour of Decision is titled ‘The Coloured World Revolution.’ He turns his sights from the political, social, and civilizational dynamics at work inside Europe, instead taking a look at how the non-Western world will impact the fate of Western culture. The final part is riveting because it seems to address the most pressing problems of our age with extreme precision. This should not come as a surprise, though, because everything that he points out as a sign of the coming crisis has only worsened in the last century.

Spengler speaks extensively of race in this final part of the book, but we should understand that he does not see race in the same terms that we do in the current zeitgeist. Spengler is not a materialist. When he is discussing race, he is not discussing race in the narrow materialist framework that modern progressives think in. He says:

But in speaking of race, it is not intended in the sense in which it is the fashion among anti-Semites in Europe and America to use it today: Darwinistically, materially. Race purity is a grotesque word in view of the fact that for centuries all stocks and species have been mixed, and that warlike - that is, healthy - generations with a future before them have from time immemorial always welcomed a stranger into the family if he had "race," to whatever race it was he belonged. Those who talk too much about race no longer have it in them. What is needed is not a pure race, but a strong one, which has a nation within it. (page 114).

It is important to keep Spengler’s understanding of race in mind as we analyze his understanding of racial dynamics.

Two wars are being fought, according to Spengler. There is the class war and there is the race war. Colonialism by the Western powers across the known world created masses of resentful people in the conquered countries. After World War I and the weakened Europe, they saw this as an opportunity to strike back at the West.

Spengler describes the invasions by Celtic-Germanic Barbarians in the late Roman Republic. Julius Caesar was unable to restore the Alexandrian Empire and after the death of Caesar Augustus, the Roman military faced mass casualties and insurrections in the frontier legions. Thus, the foreign policy of the Roman Empire immediately plunged itself into systematic defense. Spengler describes this as "the Late pacifism of a tired Civilization" (page 109). The Roman Empire could survive for centuries under a systematic defense foreign policy, but Spengler argues that the same is not the case for Western Civilization. Western Civilization spread to Australia, South Africa, and the Americas. The fragmented nature of Western Civilization meant the geo-strategic situation was (and is) entirely different because in between the colonies of Western Civilization are vast lands of non-Western Civilization. Therefore, Western Civilization could not engage in the same systematic defense Classical Civilization practiced. The end of World War I marked the beginning of the subjugation of the West to the non-Western.

Spengler points out that non-Westerners are used as a tool by Westerners in conflicts. The Jacobins mobilized the Haitian slaves for the sake of their radical policy. Similarly, the English encouraged the Native Americans to attack rebels during the American War for Independence. Spengler says that in his time, foreigners were brought into Europe as tools to be used against other Europeans. Upon first reading this, I had a difficult time quickly calling to mind historical examples of what Spengler is referring to here. This is not because I do not believe him, but rather because the rate at which non-Europeans now flood Europe has dwarfed all migration into Europe that ever occurred in the past.

All of Europe lost World War I. "It was not Germany that lost the World War; the West lost it when it lost the respect of the coloured races" (page 110).

Russia experienced both revolutions at once. The Petrine aspect of Russia, that primary occurrence of Western culture in Russian life, was killed off by the Bolshevik agitators we have spent many words reviewing. The reorientation of values away from transcendence and toward materialism placed the machine at the center of Russian life. The machine was foreign to the Russian soul, which still was in touch with the soil and the nobility of work. Without God or culture, though, there was no more nobility of work, and the new god became the inverse invisible hand of Karl Marx: historical materialist dynamics. Spengler identifies two revolutions at work here: technics and Asiatic Bolshevism. In doing this, the Russian nation severed itself from Western culture wholly and completely. Spengler identifies Japan as the only other world power that was threatening in terms of the non-Westerners against the West.

The Western tradition provided the intellectual ammunition for the non-Westerner to go after the West. Marx was European, but his thought took hold in Asia. Spengler also points to "the independence movement in Spanish America, dating from Bolivar (1811)," as "unthinkable without the Anglo-French revolutionary literature of 1770" (page 112). Spengler argues that the "Indian" sought to dominate South America completely and to eliminate whiteness. This has not panned out as he predicted.

Spengler blames the Christian missionary for sowing the seeds of Bolshevism in Africa. In addition, the Christian missionary also paved the way for the Muslim missionary in Africa. Spengler claimed that the Islamic doctrine of war and manliness was more appealing to much of Africa than Christianity, which in Spengler's assessment is viewed as merely a religion of pity. In addition, the Muslim missionary has a distinct advantage over the Christian missionary in Africa: he is not European, and therefore he is not easily identified as a white colonizer. I am certain that the leftists of today would agree with the preference for Muslims over "white Christian colonialist" missionaries. Ironically, of course, Islam has much harsher 'solutions' for what both Christians and Muslims regard as social ills and leftists worship.

Spengler summarizes the hostility of the non-Western toward the West:

This general Coloured Revolution over the whole earth marches under the disguise of very varied tendencies: national, economic, social. It directs itself now against the white governments of colonial empires (India) or of its own land (the Cape), now against a white upper stratum (Chile), now against the power of the pound or the dollar - any alien economic system, in fact. It may even be found opposing its own financial world for doing business with the whites (China), or its own aristocracy or monarchy. Religious motives also contribute: hatred of Christianity or of any form of priesthood and orthodoxy whatever, of manners and customs, world outlook, and moral. But ever since the Boxer Revolution in China, the Indian Mutiny, and the revolt of the Mexicans against the Emperor Maximilian, there will be found, deep down, everywhere one and the same thing: hatred of the white race and an unconditional determination to destroy it. (page 114)

The question, according to Spengler, is whether or not Faustian man will be able to overcome this quest for his elimination. "What resources of spiritual and material power," Spengler asks, can the Western "world really muster against this menace?" (page 114).

Spengler does not think in race in materialistic terms, but instead spiritual terms. He is speaking specifically of those willing to muster, prioritize, and breed strength, nobility, and virtue. The race of the strong, which is not constrained to certain genetic parameters, has risen and fallen throughout history. The willingness to become strong once again is what is necessary for the preservation of Western culture. However, most of the strong in Europe were slain in World War I. Spengler says that "the test of race is the speed with which it can replace itself" (page 114). The next generation fought World War II, though, wiping out the strongest Europeans from all countries once again. The strong must be willing to breed and multiply their numbers. Those who rail against this idea are the enemies of Western Culture. Spengler says "The trivial doctrine of Malthus, preached everywhere today, which extols barrenness as progress, only proves that these intellectuals have no "race," not to mention the idiotic idea that economic crises can be surmounted by an atrophied population. It is just the other way round. The "big battalions," without which there is no world policy, give protection, strength, and internal riches to the economic life also" (page 115).

The weak do not procreate because it requires courage and self-denial to build for the future, and that is what creating children is: building the future. The rootless cosmopolitans, obsessed with materialism and the ticking up of GDP, think in terms of resources and spreadsheets. They have no conception of their bloodline and their spirit triumphing over chaos and chance and marching out into history. This is what is necessary, and this is why the salvation of the West does not lie with those concerned about banal concepts like the anti-anthropocentric protection of the planet. The planet is ours to be stewards over, and if we are not strong, and the planet is not filled with the noble and cultured, the vast resources of our Earth shall go to waste.

What is the duty of woman? She is not meant to simply be a desirable object of consumption, Spengler says, but her primary objective should be to become a mother. Spengler states that women become jealous of the women who have men who they think would make great fathers. Still, he distinguishes these women from the women entrapped within progressive philistinism: "The mere intellectual jealousy of the great cities, which is little more than erotic appetite and looks upon the other party as a means of pleasure, and even the mere fact of considering the desired or dreaded number of children who are to be born, betrays the waning of the race urge to permanence; and that instinct for permanence cannot be reawakened by speeches and writing" (page 115).

Family is the goal of noble and strong peoples. This is why the enemies of the West are also the enemies of families. Anti-family policy and social conditioning have ravaged the West for over a century, and we are seeing the consequences. This comes at great cost. Spengler states "A man wants stout sons who will perpetuate his name and his deeds beyond his death into the future and enhance them, just as he has done himself through feeling himself heir to the calling and works of his ancestors. That is the *Nordic* idea of immortality" (page 115). Socialism also erodes this primordial understanding of family, because the father seeks to own his own property so that there may be a firm foundation for raising the next generation. When all property is owned by the state or the collective, the urge to create for the future is decimated. Strength and ownership go together, creating the future. Weakness and the desire to profit on what others have done leads only to collapse. He states:

The meaning of man and wife, the will to perpetuity, is being lost. People live for themselves alone, not for future generations. The nation as society, once the organic web of families, threatens to dissolve, from the city outwards, into a sum of private atoms, of which each is intent on extracting from his own and other lives the maximum of amusement - panem et circenses. The women's emancipation of Ibsen's time wanted, not freedom from the husband, but freedom from the child, from the burden of children, just as men's emancipation in the same period signified freedom from the duties towards family, nation, and State. (page 116)

Spengler laments that nearly every country in the Western world is facing declining birthrates. A century later, these birth rates are nearly below replacement rates.

Spengler also points out that now life is measured in quantity of days, rather than in quality of achievement: "Nineteenth-century medicine, a true product of Rationalism, is from this point of view also a phenomenon of age. It prolongs each life whether this is desirable or no. It prolongs even death. It replaces the number of children by the number of greybeards. It promotes the world outlook of panem et circenses by estimating the value of life by the number of its days, not by their usefulness. It prevents the natural process of selection and thereby accentuates the decay of the race" (page 116). The quality of the population degenerated, Spengler says. Eugenics is one of the most toxic ideas in the world today, but the idea of dysgenics should be thrown in the garbage bin as well. Many eugenic policies are morally and ethically dubious at best, but the active pursuit of dysgenics is just as bad. This is a difficult subject, of course, because how do we even qualify the value of a life? For life itself, it probably is not possible to do so, but we can look at the achievements within one’s lifetime to judge their contribution to the culture. In our age, birth control and being a girlboss career woman who indefinitely procrastinates child rearing is promoted. It is promoted among the would-be aristocracy most of all. It is not hard to deduce from these conditions what the outcome will be.

Spengler calls for a revitalization of barbarism. Barbarism is the race of strength that one possesses. It is not a race in the materialist sense, but rather in a spiritual one. We know this to be the case because although many Westerners are descendants of the barbarians of old, and even share their genes, we are no longer part of their race of strength. We have abdicated the ancestral spirit that Spengler claims is necessary for the reassertion of the West over its enemies. "It is dead only when Late urban pacifism, with its weary desire for peace at any price, short of that of its own life, has rolled its mud over the generations. That is the spiritual self-disarmament, following on the physical, which comes of unfruitfulness," Spengler says (page 117).

Within Germany is the only remaining hope, Spengler said, because the German people had not spent themselves in the way that other cultures had. Spengler states that "But in this people there lies, notwithstanding the devastation of the last decades, a store of excellent blood such as no other nation possesses. It can be roused and must be spiritualized to meet the stupendous tasks before it. The battle for the planet has begun. The pacifism of the century of Liberalism must be overcome if we are to go on living" (page 118).

Pacifism must be rejected and the warlike spirit must be re-embraced, for the fate of our high culture is in the balance. Prussianism, as we discussed in an earlier piece, must be re-instantiated into the population through the education of life. Spengler says, "It must be education which rouses the sleeping energy not by schooling, science, or culture, but by living example, by soul discipline, which fetches up what is still there, strengthens it, and causes it to blossom anew" (page 119). The people of the West must prepare themselves for battle, because the enemies of the west are taking up their swords as we lay down our own. Spengler emphasizes the importance of the rest of the world fearing the power of the West. Now the West is no longer feared, only hated.

“The loathing of deep and strong men for our conditions and the hatred of profoundly disillusioned men might well grow into a revolt that meant to annihilate" (page 119). This is how we must overcome the crisis. Spengler warns that the crises will become worse if the forces of racial resentment and class resentment unite with one another. Another world of sexual resentment has also sprung onto the playing field. This unification certainly occurred, and the West now faces conflicts on all fronts. These leftist forces are united against the common enemy: Western man.

Spengler concludes The Hour of Decision with:

Here, possibly even in our own century, the ultimate decisions are waiting for their man. In presence of these the little aims and notions of our current politics sink to nothing. He whose sword compels victory here will be lord of the world. The dice are there ready for this stupendous game. Who dares to throw them?

This is the end of my section-by-section coverage of The Hour of Decision, but it does not mark the end of my writing on the book. I plan to publish another piece or two to wrap it up and give my overall thoughts on the book.

Wow--this is a powerful essay--first class content! Well done!